ELECTRONIC TARGET MAINTENANCE

By Graham Mincham

This article describes a typical electronic target maintenance program. Without the assistance of Peter Hulett and the Geelong Rifle Club in Victoria, this article could not have been written. The Geelong Rifle Club has been operating the Kongsberg electronic target system since 2007. Whilst other electronic target systems have also become available in the meantime, the Kongsberg system is typical of the breed and the Geelong Club have had good experience in sorting out the maintenance issues. We are indebted for the opportunity to view the lessons learnt by the Geelong Rifle club over several years of operating this target system.

Here is how Peter describes the Geelong range: “There is a single enclosed firing point and target galleries at each of the distances 300m, 500m, 600m, 700m, 800m and 900m. Each of these galleries contains one Kongsberg electronic target. There is a 1200mm x 1200mm target at 300m, a 1800mm x 1800mm target at 500, 600, 700m, and a 2400mm x 1800mm target at 800 and 900m. Each target is mounted permanently in the frame and when not in use is covered with a vinyl weatherproof cover with zippers on both sides. At each target is a 12-volt gel battery, which powers the target. Each battery is attached to a regulated solar cell to maintain battery condition”. Figures 1 to 3 show the Geelong Clubhouse and range facility.

Figure 1: The Geelong Club House and Firing Point

Figure 2: View Downrange from a Firing Port

Figure 3: View of Shooters Position

It is a fair observation to note that the importance of good maintenance on the physical electronic target has been largely underestimated both here and overseas. When done improperly, it becomes the prime culprit for missed shots, poor accuracy and unreliable operation of the system. It is important for those bodies contemplating the purchase of electronic targets to understand this topic. Mostly this article will deal with the maintenance of the physical target, because it is subject to constant degradation due to shots passing through it. Following that, we shall look at the maintenance of the system overall, as experienced at the Geelong range.

The construction materials and how they degrade with shots passing through them, dictate the maintenance program for an electronic target. A typical long-range electronic target for centrefire rifle competition is a sandwich construction. The purpose of the sandwich construction is:

- To provide a high integrity internal acoustic chamber, suitable for efficient operation of the acoustic sensors.

- To isolate this internal acoustic chamber from outside noise sources that might interfere with the sensing of shots passing though the target.

- To isolate this internal acoustic chamber from rapid changes in temperature that might interfere with accurate location of shots.

- To maintain the integrity of the internal acoustic chamber during an extended number of shots and puncturing of the structure.

This sandwich construction on the Kongsberg targets consists of seven layers, working from the centre and outwards as follows:

- The central layer is the wooden frame with acoustic sensors typically mounted in the inside corners, and with the wiring running around the outside edge of the frame. This provides the basis for the acoustic chamber and for mounting the other layers.

- Layer two is a rubber sheet stretched over the front of the frame, whilst layer three is also a rubber sheet on the rear of the frame. This defines the front and rear surface of the internal acoustic chamber and provide a self-sealing membrane to shots. They also act as barriers to prevent debris arising from shots puncturing the outer layers and entering the acoustic chamber.

- Layer four is a thick polystyrene foam sheet on the front of the rubber sheet, whilst layer five is also a polystyrene sheet covering the rear rubber sheet. Their purpose is to provide acoustic and thermal isolation for the internal acoustic chamber.

- Layer six is a coreflute sheet covering the front foam sheet, whilst layer seven is a coreflute sheet over the rear foam sheet. Their purpose is to hold the layers together by a fixing system to the frame and of course to provide a surface to mount the aiming mark or paper target.

This construction will become clearer by referring to a series of photo’s below, dealing with refurbishment of the target.

Perforation of the target occurs over the course of multiple shots striking it. Initially these are self-sealed by the construction, but eventually the target central area, where most shots strike, is shot away and a gaping hole appears, and potentially right through the structure. Debris from the outer layers then falls through the hole in the rubber sheet and into the acoustic chamber.

The perforation of the target, particularly the central hole through the whole sandwich structure, compromises the integrity of the acoustic chamber and this in turn leads to missed shots and inaccurate plotting of shots. If allowed to progress too far this perforation of the target may lead to failure of the system and incorrect recording of shots on the shooters monitor.

Debris falling into the acoustic chamber will collect in the bottom and if it smothers an acoustic sensor, it will compromise the operation of that sensor. Moving the target regularly between the butts and target storage area disturbs this debris and increases the likelihood of this occurring.

In order to restore the integrity of the acoustic chamber and accurate plotting of shots, it is necessary to refurbish the target on a regular basis. The question of when the target needs refurbishing depends on the target size and the number of shots that have hit the target. (See Figure 4). This is a key point and probably is the most misunderstood feature of operating an electronic target system. Let us now look at how the Geelong Rifle Club have solved this and what Peter Hulett also has to say about other maintenance issues.

The Geelong Club refurbishes their Kongsberg electronic targets by the following procedure:

- The first stage is to remove the side and top covers which are held in by self-tappers screwed into the frame. (See Figures 5 and 6).

- The second stage is to remove the front layers of the target. (See Figure 7). The original Kongsbergs were held on with Velcro that used to slip after a while in the wind so that the optical centre was different from the electronic centre. Our target fronts and backs are now held on by self-tappers and mudguard washers or by plastic threads with plastic nuts. Note the debris sitting at the bottom of the rubber skin. Pieces of Corflute and cardboard that build up over time.

- The third stage is to check all wires for nicks and cuts. (See Figure 8). Any wires that were cut while the target was at the gallery would have been fixed on-site with “Scotchloks”. (See Figure 9). At this stage in a refurbishment, any cuts or Scotchloks would be replaced with a permanent solder patch.

- The fourth stage is to clean the target with compressed air. (See Figure 10).

- The fifth stage is to stand the target up and remove its back. (See Figure 11).

- The sixth stage is to carefully vacuum debris from the inside of the acoustic chamber, being careful of the sensors in the corners. (See Figure 12). Note the hole shot in the outer rubber skin. This layer must be rotated or patched to provide a new surface. Rubber can be successfully patched by using Kwik-grip or similar.

- The final stage is to replace the two outer polystyrene and core flute layers. Alternatively, if recoverable, they may be patched using polystyrene and cardboard. Each cover consists of a layer of polystyrene and an outer of Corflute or 2 glued layers of corrugated cardboard on an outer layer of corflute. A new aiming mark and centre is then glued on and the refurbished target is ready to go.

At about 3,000 rounds the mid range target requires patching of the rubber, cardboard/foam and coreflute sheets. It takes about 8 manhours to complete with a material cost of about $150.

At 6,000 to 9,000 rounds a full refurbishment is required where all of the rubber, cardboard/foam and coreflute sheets are replaced at a material cost of about $400.

Figure 4: Target Due For Refurbishment

Figure 5: Stage 1.Removing Covers

Figure 6: Stage1.Removing Covers

Figure 7: Stage 2.Removing the Top Layers

Figure 8: Stage 3.Checking for Broken Wires

Figure 9: Temporary Wire Repair by Scotchlock

Figure 10: Stage 4.Cleaning Target with Compressed Air

Figure 11: Stage 5.Removing the Back of the Target

Figure 12: Stage 6.Vacuum Debris

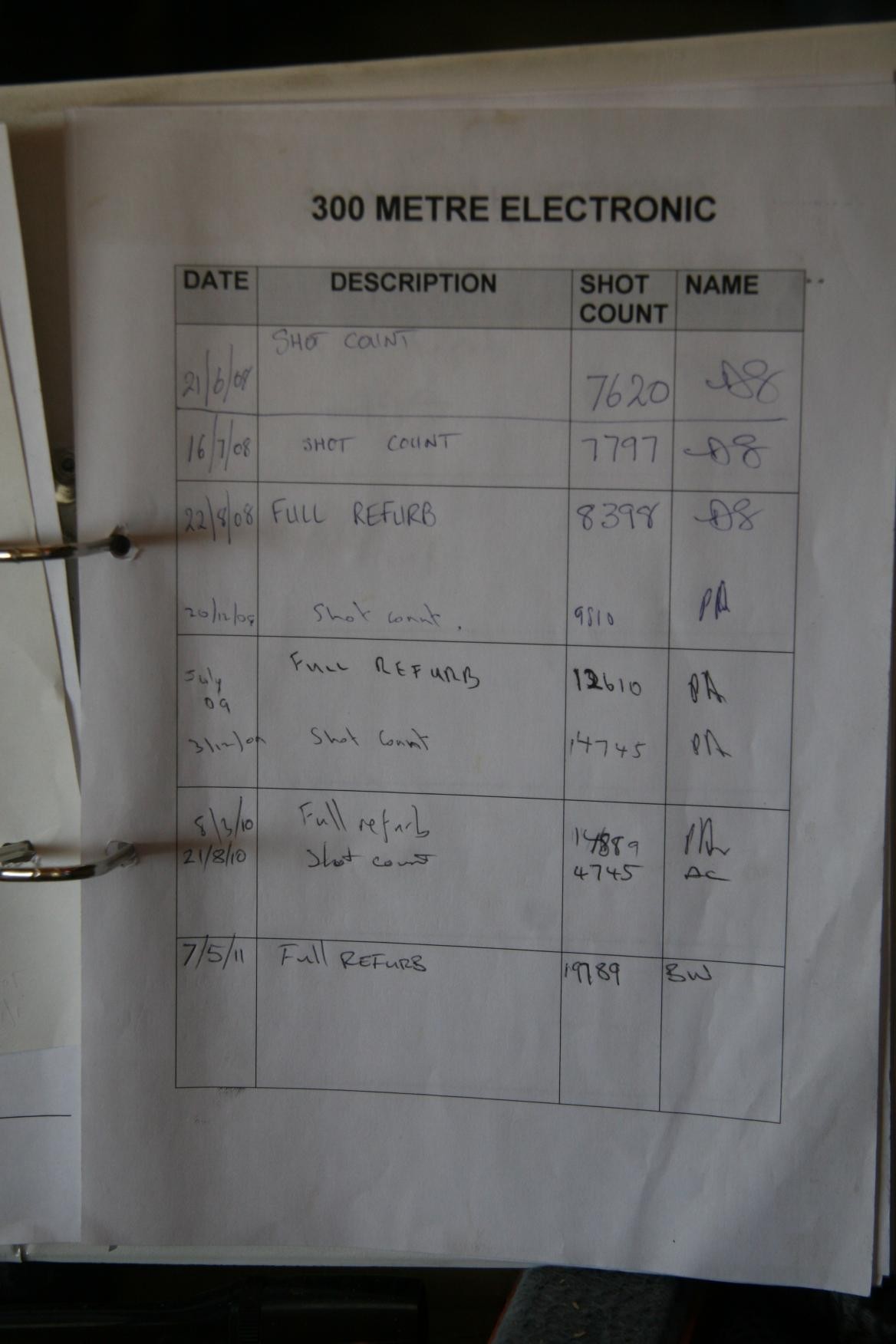

The Geelong club also keep a log of the number of shots fired on each target and a maintenance sheet recording action taken. A photo of the maintenance sheet for the 300 metre target is shown at Figure 13. Peter Hulett considers the 1200mm by 1200mm 300 metre target to be the most robust of the Kongsberg targets, and can take the most punishment before a refurbishment. The sheet at Figure 13 shows that refurbishment of this target occurs at intervals of about 4,000 to 5,000 rounds.

The 1800mm x 1800mm and the 2400mm x 1800mm target frames require more regular refurbishment at about 3,000 rounds. This is an important observation to note, particularly for those clubs contemplating using the larger frames at short range.

Figure 13: Maintenance Sheet for 300m Target

To deal with issues on the maintenance of the Kongsberg electronic target system, I put to Peter a series of questions. Here they are, with Peters response:

- How many shots do you allow on short range and long-range targets before they need an overhaul? There is quite a variation in your photos. What’s the policy?

Policy has varied over time. We started with refurbishing every 1000 rounds but experience has shown us that the 6’ X 6’ targets need to be brought back about every 3000 rounds. The 6’ X 8’ long-range targets can be left longer as can the 4’ x 4’ target. The long range targets don’t get shot out very often as the spread of shot is wider and the little 300m just keeps on going and producing accurate results even when the rubber is shot out. The important thing is to encourage members to do a regular shot count so that you can review the possible need for refurbishment. Policy and practice often differ when you are relying on volunteers to give up their time.

- How often a year (or longer) would you get a stoppage due to a shot out sensor and shot out wires?

We have never shot out a sensor. Wires may be hit once or twice a year but usually in the long-range targets.

- How often a year do you use the range? Then when you uncover the targets and “switch on”, how often would you get an immediate fault and need to fix it before you start?

The range is used Saturdays only about 48 times per year. We shoot in almost all weather conditions including those, which would close a conventional range. On less than 10 occasions per year we may get a fault on start-up, which requires the connections to be checked. Many of these failures are due to either incorrect or missing connections or components being connected in the wrong order. Since we replaced every connector with a higher–quality product the occurrence of this has been reduced.

- On how many occasions during the year would you get a stoppage to shooting, that requires your maintenance person to fault find and fix the problem? How long can this typically take?

A typical breakdown during a shoot requires the following procedure. First we do a full check of the system, which may take 10-15 minutes. Most times that works. If a target is still not working then that target is taken out of service until it can be looked at. On normal ranges this is less of a problem as they have multiple targets but at Geelong it means we must move to a different distance. If the breakdown occurred during an important shoot other than a club practice then the target would be dropped out of its frame and checked for physical damage. We can drop a target, splice a wire and have the target back operating in less than 20 minutes. Twice, if my memory serves me correctly, the whole system failed and we had to stop shooting. On each of these occasions, lightning strike and torrential rain, a conventional range would not have been operating.

Perhaps if I explain the set-up process in more detail.

The targets to be used must be connected and this requires plugging in a cable at the target and at the battery/cable box. We had many problems with these connectors until we replaced those Kongsberg supplied with Amphenol Ecomate type (Kongsbergs are now supplied with Eco-mate plugs). Even still, if people are not careful they may not connect properly or even forget to connect at all. Those members setting up are supposed to check the LEDs on the target circuit board to make sure that all is functioning but sometimes that doesn’t happen. In fact the original Kongsbergs came with metal circuit board covers so that you couldn’t see the LEDs at all. We replaced them with Perspex and I notice the later Kongsbergs come with Perspex covers. The furthest target to be used must be connected first and then the next and so on. Why I don’t know.

At 300M we have what Kongsberg calls its “external target electronics” and this box includes the target electronics for the 300M target and interrogates each target on line to see if it has a shot. This unit needs to be powered up and then a switch is thrown that connects it to the other targets. If communication is established with any other target an LED lights up. There is no information as to how many targets are on line or indeed which targets are on line. You can only tell by firing a shot.

Once this down range sequence is complete, the Signal Distribution Unit (SDU) at the firing point is powered up and this starts up the monitors. The monitors are the “smart” part of the system and it is in the monitors that the software operates. If the system is to fail at set-up you really don’t know until a shot is fired and you discover that a particular target is not responding. When this happens our procedure is to switch off the SDU, go downrange to the 300m target and switch off the external target electronics and then check the offending target. Reconnect the cable and then repeat the start-up process. It is probably not all necessary but remember we are now ready to shoot and we don’t want to waste time.

On Prize meeting and Pennant days we would test fire on all targets before the commencement of shooting so our guests are not inconvenienced.

Occasionally a target will stop working during a shoot and the above process is repeated. Usually this clears the problem unless there is a fault with the target.

- What is the most common cause of a stoppage to shooting due to any failure? How long does it take to fix?

Electronic glitch with no obvious reason in a single target. Requires a check, which means that somebody needs to drive down range. Say 10 minutes. When we have a strong wind from the NW that blows directly onto the back of the targets the likelihood of target failure increases as the back of the target blows in and partially closes the acoustic chamber. We can protect the targets from buffet to some degree by screwing plyboard sheets onto the target supports but these get shot out quickly.

- What other less common things have gone wrong and how often, for example rain damage, lightning strikes, animal (sheep) damage, insect infestations. We only need to cover stoppages due to these kinds of things.

Lightning hit us once and burnt out a component in a circuit board. If we have a spare board available we can change it in about 30 minutes. We have never had damage by rain but the targets stopped working once in a heavy rain storm but worked fine the following week (maybe a humidity problem) and as it was just a club practice we decided to abandon rather than get wet trying to figure it out. Sheep ate the wire on the 900-metre target in 2010 and we repaired it. It was again eaten in 2011 so the repair now includes greater protection for that wire. The insects are in the targets all the time and do not normally cause a problem as they are outside the acoustic chamber. We did have one situation where a rat or a bird built a nest between the back of the target and its protective plyboard sheet. This pushed the back of the target into the acoustic chamber.

- How many people do you have on standby in the club to fix these things on the day? How many hours a year would they actually spend fixing the system?

There are two members of the club who can trouble shoot and attempt to diagnose faults. Because I am away 5 months of the year the bulk of the work falls to one person. This is why our refurbishment program gets out of whack. How many hours a year? How long is a piece of string? Fifteen minutes or so to drive downrange and reboot. Actually we don’t spend much time on electronics because we don’t understand it all that well. We work on replacing components until we find a solution. Say 10 or so hours a year.

- How many people do you have refurbishing targets? How many hours does this take, and how many hours a year would they expend on this?

Refurbishing is a much less technical job and we have a number of people with the skills for this. Is has fallen to the same 2 or three in the past and one target takes about 8 man-hours to redo. Each target gets done about once per year and the work has been done during the week. We are trialling a new system now where a target is brought back and the plan is to refurbish it in one Saturday afternoon during shooting. The repair area is about 10 metres from the shooting shed so this is feasible and we did it with the 300M target. This way we get a lot more members involved in providing the 8 man-hours.

The Geelong Club have learned from experience, the need to keep a log of the number of shots fired and to keep a maintenance record for each target. Peter Hulett has also given us some insight into the other issues of system maintenance. These are crucial lessons learnt and we can all benefit from this.

The installation at Geelong, of course, is very different to other ranges around the country, because it was purpose built for electronic targets and shooting is conducted from an indoor fixed firing point. Many of the lessons presented here will be of interest to clubs shooting on existing ranges in the open and where there is one target gallery and multiple firing points.

In these other cases there will be additional causes of system breakdown due to factors such as the monitors being deployed outside in the weather and being subject to handling wear and tear. Additionally if the targets need to be moved back to a storage area, then additional failures will arise due to this activity. Perhaps it should be pointed out at this stage that these targets are very heavy, ranging from about 60 kilograms from the small target to about 80 kilograms for the largest one. They are not easy to manhandle and most clubs should consider aids such as a target trolley with wheels to move them about, similar to the arrangement on the Anzac Rifle Range.

It is hoped that this article will be of benefit for clubs considering the purchase of electronic targets. It is also recommended that the NRAA website also be viewed to see the latest updates on electronic target matters as released by the NRAA committee responsible for this activity.

G.Mincham March 2012 (Reproduced with permission 2013)